Thorold Charles Reep was born in 1904 in the small town of Torpoint, Cornwall, on the south west of England. At the age of 24, he joined the English Royal Air Force to serve as an accountant, where he learned the necessary mathematical skills and attention to detail that he went on to employ throughout his career. During World War II, he was deployed in Germany, and would eventually be awarded the rank of Wing Commander.

Thorold Charles Reep (1904-2002) - Source: The Sun

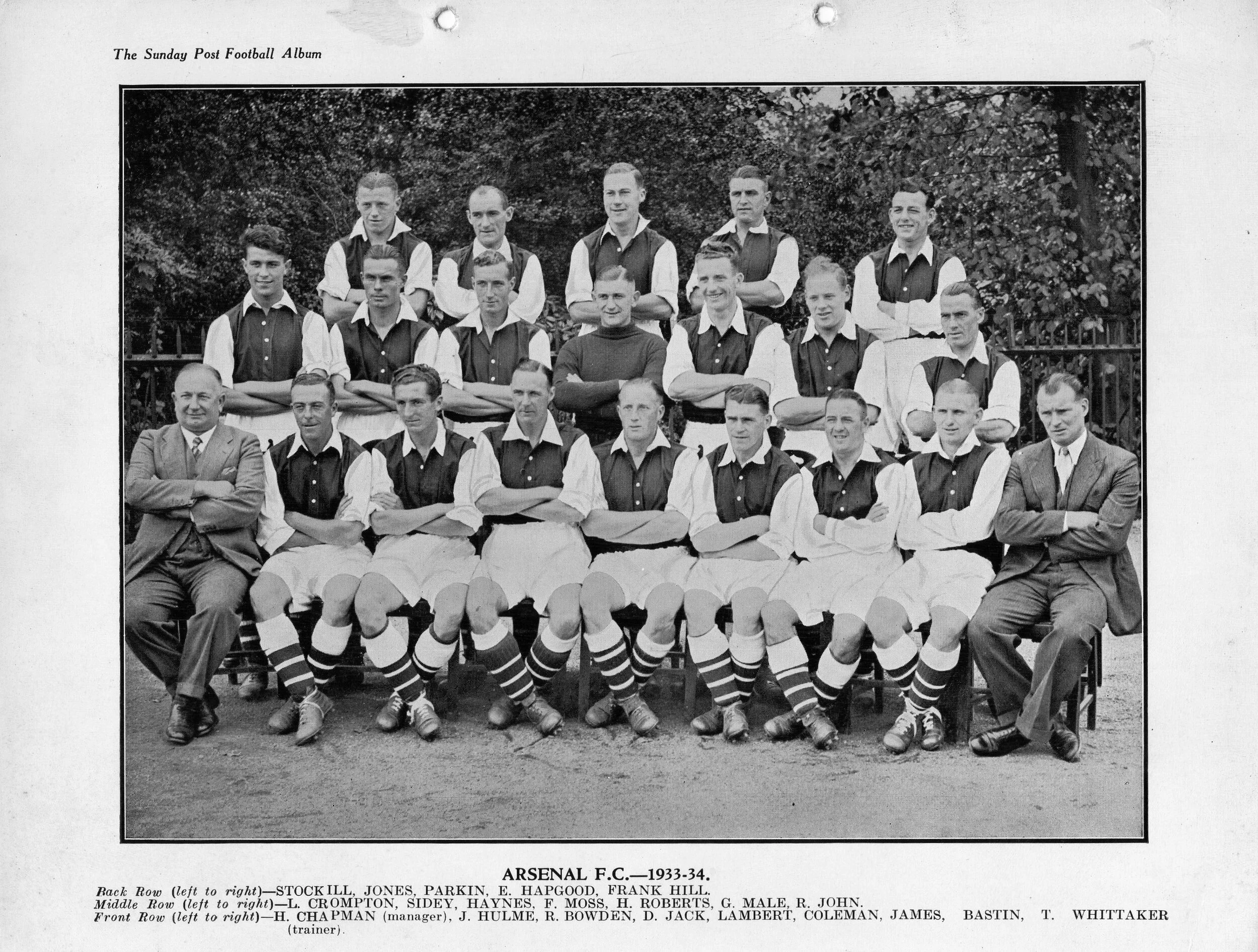

From a young age, Reep was a faithful supporter of his local club Plymouth Argyle and would frequently attend matches at Home Park Stadium. However, his relocation to London after joining the Royal Air Force gave him an opportunity to attend Tottenham Hotspurs and Arsenal matches. In 1933, Arsenal’s captain Charles Jones came to Reep’s camp to talk about the analysis of wing play being used by the London club, which emphasise the objective of wide players to quickly move the ball up the pitch. The talk deeply inspired Reep, who soon became a keen enthusiast of Arsenal’s manager Herbert Chapman and his attacking style of football. This was the start of Reep’s passion for attacking football and its adoption across the country.

Arsenal FC 1933 squad including Herbert Chapman and Charles Jones - Source: Storie Di Calcio

In March 1950, during a match between Swindon Town and Bristol Rovers at the County Ground, Reep became increasingly frustrated during the first half of the match by Swindon’s slow playing style and continuously inefficient scoring attempts. He took his notepad and pen out at half time and started recording some rudimentary actions, pitch positions and passing sequences with outcomes using a system that mixed symbols and notes to obtain a complete record of play. He wanted to better understand Swindon’s playing patterns and scoring performance and suggest any possible improvements needed to guarantee promotion. He ended up recording a total of 147 attacking plays by Swindon in that second half of their 1-0 win against Bristol.

Swindon Town vs Bristol Rovers 1950 Match Report - Source: Swindon Town FC

Using a simple extrapolation, Reep estimated that a full match of football would consist on an average of 280 attacking moves with an average of 2 goals scored per match. This indicated an average scoring conversion rate of only 0.71% per goal, suggesting only a small improvement was needed for a side to increase their average to 3 goals per game from just 2.

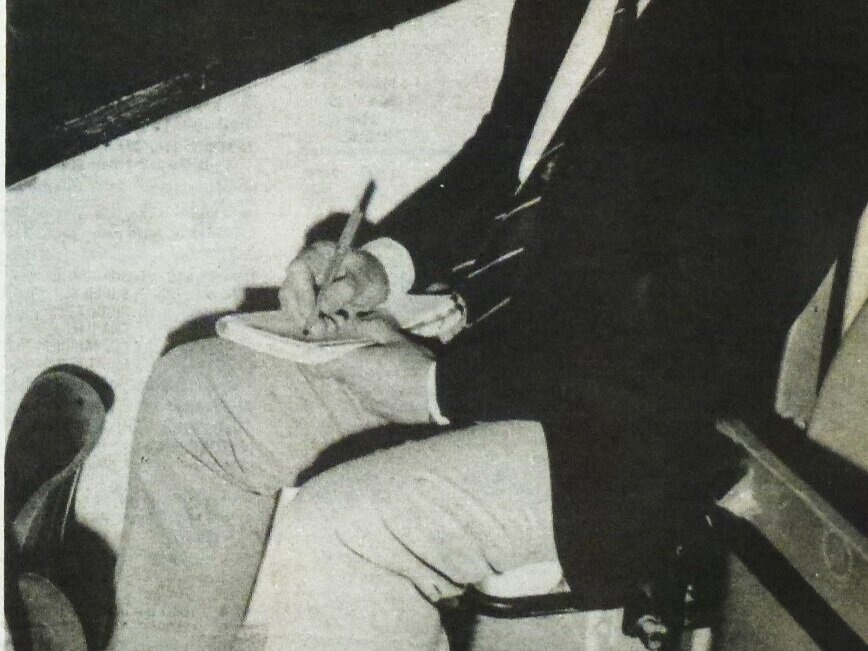

In the years that followed, Charles Reep quickly established himself as the first performance analyst in professional football, as he witnessed how the information he was collecting was being used to plan strategy and analyse team performance. He never stopped developing his theory of the game, watching and notating an average of 40 matches a season, taking him around 80 hours per match. He was often spotted recording match events from the stand at Plymouth's Home Park wearing a miner's helmet to illuminate his notebook, meticulously scribbling down play-by-play spatial data by hand.

In 1958, he attended the World Cup in Solna, near Stockholm, and produced a detailed record of the total number of goals scored, shots and possessions during the final. He wanted to provide an objective count of what took place in that match, away from opinions, biased recollections or a few single memorable events on the pitch. He produced a total of fifty pages of match drawings and feature dissection that took him over three months to complete.

Match between the domestic champions of England (Wolverhampton Wanderers) and Hungary league winners (Budapest Honved) in 1954. Stan Cullis declared his team as “champions of the world” after their 3-2 victory. This provoked a lot of criticism and inspired the creation of the official European Cup the following season - Source: These Football Times

The real-time notational system Charles Reep developed took him to Brentford in 1951. Manager Jackie Gibbons offered him a part-time adviser position to help the struggling side avoid relegation from Second Division. With Reep’s help, Brentford managed to double their goals per match ratio and secure their Division spot by winning 13 of their last 14 matches.

The following season, his Royal Air Force duties moved Reep to Shropshire, near Birmingham. There he met Stan Cullis, at the time manager of the successful and exciting side Wolverhampton Wanderers. Cullis offered Charles Reep to take similar advisory responsibilities at his club to the ones he successfully undertook at Berntford. Reep not only brought with him his acquired knowledge from the analysis performed at Swindon and Brentford but also a innovative, real-time process that provided hand notations of every move of a football match, together with subsequent data transcription and analysis. As a strong believer of direct attacking football, Reep’s work only reinforced Cullis’ preestablished opinions of how the game should be played.

Stan Cullis, Wolverhampton Wanderers manager from 1948 to 1964 - Source: Solavanco

In his three and a half years at Wolves, Reep helped the club implement a direct, incisive style of play that consisted of very few aesthetics (i.e. skill moves) but instead took advantage of straightforward, fast wingers. Square passing by Wolves players became frowned upon by Cullis and the coaching team. During this time, the concept of Position of Maximum Advantage (POMO) began to emerge, describing the area of the opposition’s box in which crossed should be directed to in order to increase the chances of scoring. Under the Reep-Cullis partnership, Wolves achieved European success in what was then the European Champions Cup competition.

In 1955, Charles Reep retired from the Royal Air Force and was offered £750 for a one-year renewable contract by Sheffield Wednesday to work as an analyst alongside manager Eric Taylor. He ended up spending 3 years at Sheffield Wednesday, achieving promotion from Division Two in his first season at the club. On his final season at the club, his departure was triggered by the disappointing results by the team, and saw Reep point fingers at the club’s key player for refusing to buy into his long-ball playing system. During the remaining of his career, his direct involvement with clubs became a lot more sporadic. Nevertheless, he managed to help a total of twenty three managers from teams such as Wimbledon, Watford or even the Norwegian national team understand and adopt his football philosophy.

Over the years away from club roles, Charles Reep continued to investigate the relationships between passing movements, goals, games and championships, as well as the influence that random chance has on those variables. He was keen to continue to develop his theory by summarizing all his notes and records he had been collecting since 1950. During this analysis, Reep developed an interest in probability and the law of negative binomial, which he applied to his dataset. His analytical methods eventually became public after he shared his notes with News Chronicle and the magazine Match Analysis.

These publications demonstrated that Charles Reep had discovered insights of the game not previously analysed. Some of these suggested that teams usually scored on average one goal every nine shots or that half of the goals scored came from balls recovered in the last third of the pitch. One of his most famous remarks was to suggest that teams are more efficient when they reduce the time they spent passing the ball around and instead focus on lobbing the ball forward with as few number of passes as possible. He was a firm promoter of a quicker, more direct, long-ball playing style.

Reep followed a notational analysis method of dividing the pitch into four sections to identify a shooting area approximately 30 metres from the goal-line. This detailed in-event notation and post-event analysis enabled him to accurately measure the distance and trajectory of every pass. Amongst his findings, he discovered that:

It took 10 shots to get 1 goal

50% of goals were scored from 0 or 1 passes

80% of goals are scored within 3 or less passes

Regaining possession within the shooting area is a vital source of goal-scoring opportunities

50% of goals come from breakdowns in a team’s own half of the pitch

In 1953, Reep went on to publish his statistical analysis of patterns of play in football in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. In his paper, he analysed 578 matches to assess the distribution of passing movements and found that 99% of all plays consisted of less than six passes, while 95% of them consisted of less than four. These findings backed Reep’s beliefs of reducing the frequency of passing and possession time by moving the ball forwards as quickly as possible. He wanted that the truth he had discovered dictated how teams play.

Manual notational analysis prior to the introduction of technology - Source: Keith Lyons

From his first analysis of the 1950 Swindon Town match against Bristol Rovers all the way to the mid-1990s, Charles Reep went on to notate and analyse a total of 2,200 matches. In 1973, Reep analysed England's 3-1 loss against West Germany in the 1972 European Championship to vigorously protest the “pointless sideways” passing style of play adopted by the Germans. In that match, the Germans had outplayed the English with a smooth, passing style of football that was labelled at the time as “total football”. Reep attempted to argue against the praise this new passing style of play had received across the continent by implying that it lacked the attractiveness demanded by fans as it placed goal scoring as a secondary objective in exchange for extreme elaboration of play. Instead, he pushed forward his own views regarding the use of long balls and suggested that, even though they less frequently found the aimed player, they brought unquestionable gains. He stated that, based on his analysis, the chance generation value of five long passes missed was equal to five of them made.

Swindon Town vs Bristol Rovers 1950 Programme - Source: Swindon Town FC

Most of Charles Reep’s analysis supported the effectiveness of using a direct style of football, with wingers as high up the pitch as possible waiting for long balls. This approach to the game a had significant influence in the English national team between the 1970s and 1980s, when the debate of the importance of possession had become the central topic of conversation amongst FA directors. Reep, often described as an imperious individual intolerant of criticism, argued against the need for ball possession, contrary to the philosophy backed by then FA’s technical director Allen Wade.

It was not until 1983, when Wade was replaced as technical director by his former assistant Charles Hughes – a strong believer of long ball play – that Reep’s direct football ideology became the new FA's explicit tactical philosophy of the English game. Hughes saw in Reep’s work an opportunity to redefine the outdated ideals of the amateur founders of the FA and introduce his own mandate across the whole English game. This mandate consisted on a style of play that focused on long diagonals and physicality of players. As a result, technically gifted midfielders found themselves watching how the ball flew over their heads as they struggled with overly physical challenges.

Charles Hughes, The FA’s former technical director of coaching - Source: The Times

Controversy And Criticism

Charles Reep’s simplistic methods have been, and continue to be, critised by many football fans and analytics enthusiasts. One critic indicated that while his study assessing passing distribution showed that almost 92% of moves constituted of less than 3 passes, his dataset only contained 80% of the goals, and not 92%, from these short possessions. This contradicts Reep’s beliefs by illustrating that moves of 3 or fewer passes were in fact a less effective strategy to score goals. Additionally, it also demonstrated that Charles Reep’s argument that most goals happened after fewer than four pass movements was simply due to the fact that most movements in football (92% from his dataset) are short possessions, thus it would be understandable that most goals would be scored in that manner.

Similarly, his study did not appear to take into consideration differences in team quality. Evidence of this can be seen in that the World Cup matches he analysed, which contained double the amount of plays with seven or more passes than those he recorded from English league matches. The indication suggest that Reep missed the fact that a higher quality of the game in a higher level competition, such as the World Cup, with better players available, seemed to provide longer passing moves than in English football league matches where the average technical quality of players would be inferior. Furthermore, critics have also added that none of Reep’s analysis takes into consideration any additional factors to playing style, such as the level of exhaustion exerted on the opposition by forcing them to chase the ball around through passing.

Reep’s character and very strong preconceived notions could have prevented him from investigating alternative hypotheses that did not agree with his philosophy of direct football. He was often described as an absolutist that wanted to push his one generic winning formula. This caused most of Reep’s analysis to be ignorant of the numerous essential factors that can affect a match’s outcome. Critics have often labelled Reep’s influence on the philosophies applied to English football and coaching styles for over 30 years as “horrifying”, due the fundamental misinterpretations Reep committed throughout his work. As previously stated, one of these consisted on applying the same considerations and level of weighting to a match by an English Third Division team than to a match in the World Cup. He paid no attention to the quality of the teams involved, ignoring potentially valid assumptions that a technically poorer team may experience greater risks when attempting to play possession football. Instead, he followed his own preconceptions, such as assuming that teams should always be trying to score, when in reality teams may decide to defend their scoreline advantage by holding possession.

Aside from the criticism for his poor methods and misinterpreted finding, Reep has also been recognised for the new approaches he introduced to the analysis of the game. He was one of the first pioneers to show that football had constant and predictable patterns and that statistics give us a chance to identify what we would otherwise had missed. He initiated the thinking around the recreation of past performance through data collection, which could then inform strategies to achieve successful match outcomes. While he might not have been an outstanding data analyst, Charles Reep was a great accountant with great attention to detail and ability to collect data.

The approaches he introduced have significantly evolved since Reep’s first notational analysis in 1950. Technologies and analytical frameworks developed since the 1990s have facilitated the emergence of video analysis and data collection systems to improve athlete performance. From the foundation of Prozone in 1995 that offered high-quality video analysis to the appearance of Opta Sports or Statsbomb as global data providers capturing millions of data points per match, the field of notational and performance analysis in football has evolved in line with the technological revolution of the last few decades. The popularity of big data and the growing desire of data-driven objectivity has become important priorities within professional clubs when aiming to gain competitive advantage in a game of increasingly tight margins. Reep’s work initiated the machinery that is today an ecosystem of video analysis software, data providers, analysts, academia, data-influenced management decisions and redefined coaching processes that constitute a key piece of what modern football is today. While none of these elements can win a match on their own, they surely have been making crucial contributions in providing clubs with those smallest advantages that make the largest of differences.

Citations:

Instone, D. (2009). Reep: Visionary Or Detrimental Force? Spotlight On Man Whose Ideas Cullis Embraced. Wolves Heroes. Link.

Lyons, K. (2011). Goal Scoring in Association Football: Charles Reep. Keith Lyons Clyde Street. Link.

Medeiros, J. (2017). How data analytics killed the Premier League's long ball game. Wired. Link.

Menary, S. (2014). Maximum Opportunity; Was Charles Hughes a long-ball zealot, or pragmatist reacting to necessity? The Blizzard. The Football Quarterly. Link.

Pollard, R. (2002). Charles Reep (1904-2002): pioneer of notational and performance analysis in football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20(10), 853-855. Link.

Pollard, R. (2019). Invalid Interpretation of Passing Sequence Data to Assess Team Performance in Football: Repairing the Tarnished Legacy of Charles Reep. The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 12, 17-21. Link.

Reep, C. & Benjamin, B. (1968). Skill and chance in association football. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 131, 581-585.

Sammonds, C. (2019). Charles Reep: Football Analytics’ Founding Father. How a former RAF Wing Commander set into motion football’s data revolution. Innovation Enterprise Channels. Link.

Sykes, J. & Paine, N. (2016). How One Man’s Bad Math Helped Ruin Decades Of English Soccer. FiveThirtyEight. Link.